About 45 seconds into the evaluation, the ER doctor said, “Should we resuscitate him?” Following the blank stares on my and my brother’s faces, he went on, “You know, you really need to think this through. If, God forbid, something happens, would you want us to do everything we can? And think about what he would want if, God forbid, something happens. It’s not about what you want, but what he would want. What would his 40-year-old self, 50-year-old self, 60-year-old self have wanted? What would he think of himself with dementia? Would he want to live like that? You know, if, God forbid, something happens.”

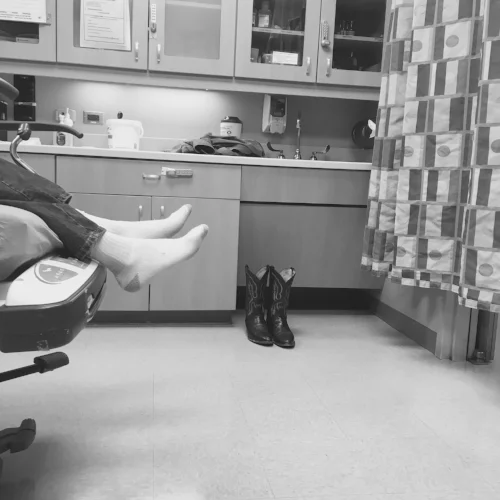

Well that was fast. Not even a minute into the evaluation and the doctor suggested we go ahead and let my dad go. The injuries that landed him in the ER on Sunday night did not appear to be life-threatening. He’s 75. Memory loss is his only known ailment. And yet, this doctor, who had never known my family before that moment, suggested we consider not saving our dad’s life if, “God forbid, something happens.”

I know it’s routine to ask resuscitation questions. I get that it’s protocol. But the pressure he was applying was real—not extreme, but very real. And it didn’t stop there.

The next day an investigative procedure was suggested by my dad’s new doctor. Though not urgent, the procedure would give us important information, determining the course of treatment. This doctor said, “If he was my parent, I’d have the procedure done. But most likely, the department that does the procedure will push back. They’ll say something like, ‘Do you really want to do this? I mean with his quality of life and all? Do you want to put him through all that when the results won’t improve his other conditions?’”

Wow. His quality of life? The man’s memory is impaired. That is all. I don’t think it’s time to withhold other treatment or let him go. And yet, within 24 hours of his admittance, one doctor had implied that and another said to expect it again.

Lucky for my dad, his daughter has a fierce conviction of the sanctity of human life and I understood these subtle nudges right away. But what about family members who’ve never considered the value of life or the end of life? What about family members who have actually run out of patience for their loved one’s ailments? What about those who think people with terminal illness have a duty to die?

And lest you think that is extreme, I have actually been told by another family member that my dad has indeed a “duty to die.” The words were spoken out of love and in consideration of the fact that my family of six has radically altered our lives to move here to care for my dad. They were meant in sympathy, to communicate that our young family shouldn’t have to shelve our dreams for him. Did this family member really believe that those with memory loss should be willing to be put down like an ailing pet because they’re draining the resources of the rest of the family?

This is the mood in America right now. If life is inconvenient, snuff it out. On either end of the spectrum—be it the beginning of life or the end—if you didn’t plan for it, you should end it.

While I recognize that my dad’s doctors were far from offering to assist in his suicide (that’s not yet legal in Colorado), they were also far from creating in me a sense that they see his life as valuable and worth saving or improving. This was a small taste, provided in a brief visit—making me think this mood must indeed be pervasive throughout our healthcare culture. The fact that Proposition 106 (a physician-assisted suicide ballot measure) is on Colorado’s ballot indicates that the culture of death is gaining momentum in our state.

I shudder to think what the doctors will suggest to me after election day.